Christian Beamish's Voyage of the Cormorant

Christian Beamish is a surfer, shaper and writer who is the author of The Voyage of the Cormorant. He lives in Carpinteria, CA, with his wife Natasha and their two children, where he shapes boards professionally and is an editor at The Coastal View News. He was previously an Associate Editor at The Surfer’s Journal.

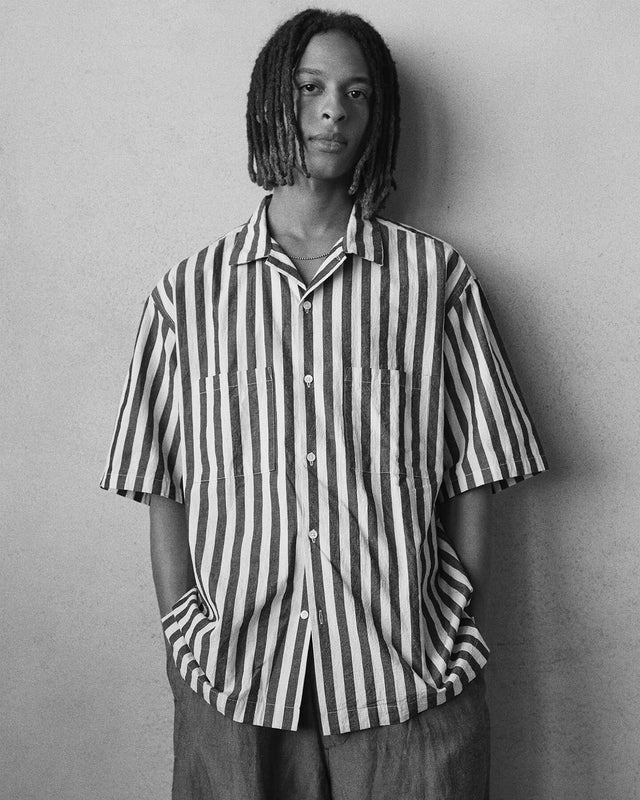

Christian at Maverick's, photo by Todd Glaser

Phil Ayers for Pilgrim recently hopped on the phone with Christian to talk about his surfing, shaping and writing, along with his epic sailing voyage down the coast of Baja.

PA: Can you tell us a bit about where you grew up and when you first got into surfing?

CB: There have been a number of chapters, but I spent my early life growing up in Newport Beach, California. I’m now 50 years old and I always mark the age of 10 as when I started to consider myself a surfer. Before that, I was doing a weekends-on-the-boogie-board-with-my-Dad kind of thing. I guess that would’ve been through the mid-70s. But by about ‘77-’78 I had surf posters all over my walls, and surfing was all I wanted to do.

PA: Was your Dad a surfer?

CB: Well, not exactly. He was a bodysurfer. He was an LA County lifeguard in the early 50s, during the golden era. He was buddies with all the surfers, but he would tell a funny story (I guess it wasn’t so funny at the time), about getting knocked out cold by the actor Peter Lawford who was riding a redwood plank at Malibu. I was telling this story to Peter Cole over in Hawaii and Peter goes, “Oh, Lawford was a menace!”

So, my Dad got knocked out cold surfing Malibu in ‘50 or ‘51 and I guess it just kind of put him off surfboards, but he was a great bodysurfer. He always kept his Churchill fins in the trunk and told another story of bodysurfing from second-reef Brooks Street in Laguna Beach on a big south swell, coming all the way across and just breaking into laughter because he was going for so long. I always loved that story.

So I was raised in this kind of lifeguarding, waterman’s household. We weren’t necessarily boat people, but lots of beach days, lots of bodysurfing... just lots of time spent in and around the water. And then I got a boogie board and I distinctly remember pulling into closeout tubes. Late one summer evening—we get these high tides in summer at sundown—I was on this little boogie board and I just remember cutting left and getting fully piped. I was literally breathing in the tube. I must’ve been eight years old or something, and just said to myself “Oh my god! Did that just happen?”

My Grandpa was a Navy captain in WWII. He was another bodysurfer and was arthritic, so he liked to be in the water to help his arthritis. So I also have these fond memories of us bodysurfing these big beach break closeout whompers together when I was a little kid, too.

When Tom Curren was coming onto the scene, like a lot of people, I was just like “Oh my god, I wanna be like him.” But I also had a big thing for Rabbit Bartholomew and that Aussie school of surfing. I soon started riding boards from Greg Pautsch. He made McCoy Surfboards USA out of Newport Beach. Most of the Newport guys back then rode McCoys, and Stussys were also super popular around that time. I surfed NSSA contests but I wasn’t so great at those. I’d just get nervous and not be in the right place. It just never really clicked for me competitively. But I soldiered on and just kept at it, and sometimes I’d get third or something…

PA: And when did writing come into the equation for you as a young surfer?

CB: I was really into Surfer Magazine. I look back on it now and maybe some of it was a bit hyperbolic, but a lot of the writing was just core and raw, transmitting the stoke of surfing through words. And there was just something about that that really hit me. And I carried that with me.

When I read Kerouac, I guess like you do in high school, and Hemingway, I was really energized by them. I had some summers in the High Sierra in a similar environment to what Karouac describes in Desolation Angels, and was just blown away by the magic of nature and the way these writers could capture it.

I worked at the school newspaper in high school, and I remember I wrote a review for a band called Electric Kool-Aid. And I guess it had some sizzle, because I remember my classmates were like “woah, that was rad!” And that’s really when I first started to feel the magic of writing and the power of the written word.

It would’ve made sense to just go to college and keep writing, but you know, without getting too deep into it, with my mom and dad being apart and the family situation being what it was, I was carrying a bit of a load. And my hometown of Newport Beach, as wonderful a place as it was to grow up, was a pretty dog-eat-dog social scene without a lot of ambition. A lot of cocaine, too. I was lucky to not go down that path, but I still saw it and was exposed to a lot of destructive partying back then. A lot of the kids in Newport were doing the same thing, going to community college, working at a pizza joint or something, living in a party house down by the beach, etc… and I didn’t want to follow that same program.

Christian Beamish, Baja, 2019, photo by Russel Holiday

And so, as you read in the book, and admittedly in a sort of naive and romanticized way, I enlisted in the Navy. I was looking for something real. So I enlisted in the U.S. Navy and I did fine, and learned a hell of a lot, and got an Honorable Discharge after four-and-a-half years.

PA: Where were you stationed?

CB: Boot camp was in San Diego, and then I did training to be in the Seabees—Navy construction, U.S. Naval Construction Battalion One was my unit. I was a Steelworker, all 155 lbs. of me, just a noodle of a kid. (I finished physically growing in the Navy, going from 5’11 to just under 6’4” and 182 lbs.) I was at Port Hueneme, not too far from where I live today on the coast near Oxnard, which is where I wanted to stay. But of all places, luck of the draw would have it that I then got stationed in Gulfport, Mississippi, which was a kind of death for me at the time. But the saving grace of it was that I was in the mobile construction battalion. We spent six months in Mississippi going to the rifle range, getting certified in welding, doing various trainings, etc., and then we would deploy overseas for eight-months.

So less than a year into the Navy, I was in Rota, Spain across the bay from Cádiz, on the south coast of Spain. And there were all types of cool little wind-swell beaches and, once again, I was surfing. Then I fell in with some Spanish surfers and we ended up traveling all over the place in search of waves and it was really, really cool.

In retrospect, even those six-months stints in Mississippi, I surfed some strange little island waves in Alabama, I surfed Pensacola on those beautiful white-sugar-colored beaches. And also, me, this kid from Newport Beach, got to hang deep in New Orleans. My girlfriend at the time had a friend who was dating a dude who was in the same circle as someone who kind of brushed shoulders with the Neville Brothers. Now I’m not saying I was rolling with the Neville Brothers, but I did get to experience the “real” New Orleans and came into contact with people I had never been exposed to back in Orange County.

I was grateful for that experience in the South and got to go on a lot of cool adventures during that period of my life—as best I could within the confines of the U.S. Navy (and it was very confining). But I did it, and I learned a lot: how to build things, fix things, work with my hands, etc., and got that “real” experience I was seeking in sense.

I was on the Cape Verde Islands on a little detachment and that was probably the pinnacle experience. We were a small detachment of guys building a schoolhouse and working with Cape Verdean soldiers, which was super cool. That was in 1991, because right after, I was called to go support a Marine division in Saudi Arabia during the first Gulf War, which I also touch upon in the book.

On the ship from Norfolk, VA to Cape Verde, I was dismayed to see all the trash being thrown overboard. Apparently, a regulation called for the trash to be put in these large paper sacks— the idea being that the paper would then disintegrate, be more “eco”—but the guys just put the black plastic trash bags into the paper sack and pitched it. And I’m just like, “What the hell am I seeing?”

Then the goddamn war and I realized “man, this is not something I want to be a part of.” But I was in it, and no matter how conflicted I felt, I had raised my hand and enlisted, it was my responsibility—so I just kind of kept my head down and did my time so to speak. I got out, and then I went surfing.

PA: I don’t blame you. Did you go on a trip of some sort?

CB: Yeah, I reconnected with an old friend and we went to the Philippines, down to a now famous spot called Cloud Nine, but back then, we didn’t see another Westerner for a good month or so. When I got home from the Navy and before I went traveling, I went down to 54th street to check the waves, and the same crew I’d grown up with was still down there doing the exact same thing. And I love those guys, but I was struck by how much had happened in my life in the past five years, and how absolutely nothing had changed at home.

So my buddy Dave and I went surfing in the P.I., Indo, West OZ, and New Zealand for about six-months, and when we returned I went to the community college in Costa Mesa, Orange Coast College. I registered for classes, then as I walked the campus to see where everything was, I kind of realized that I would be doing the same old thing after all, anyway—renting the room, working the job, partying in the town. So right then, not 30 minutes after registering for classes, I went back to the office, dis-enrolled, got my money back, and arranged a Greyhound bus ride to Santa Cruz that same day.

Christian, Santa Cruz - 1999

I had a good friend from Newport Harbor High School who’d gone off to college in Santa Cruz, and he’d always said I could crash on his couch. So I called him and he picked me up from the bus stop—two boards, a backpack, and a bike. My mother (God bless her), pretty much screamed at me: “You can’t choose your college based on the surf!”

“The beauty of it is,” I told her, “you can.”

I went to Cabrillo College for two years and then transferred to UC Santa Cruz and studied literature. After a couple of tries I was accepted into the creative writing program. When I graduated I felt I needed more practice, so I applied to the graduate writing program at San Francisco State and got an MA in fiction in 2001. I fell back on my Navy veteran status and landed myself a park maintenance job with the county of Santa Cruz, driving up to SF State once a week for writing workshops. I wrote a surfing novel for my thesis, and then quit the parks and went on another big surf trip—a bike mission down the West Coast of Ireland with a 6’6” round pin single fin I’d shaped and painted in an Aboriginal motif, heavily influenced by Santa Cruz weed and Wayne Lynch’s segment in Litmus.

I met Jesse Faen at a Masters’ event in Bundouran (that was a week-long pub crawl between ragged surfs in howling onshore wind) and he invited me to come up to Derek Hynd’s surfing festival in the Outer Hebrides. Tom Curren was there, Skip Frye, Kassia Meador, Joe Curren, Hans Hagen—all these great people. And we had a magical ten days up there, just traipsing across the Hebridean countryside surfing remote beaches in the slate grey North Atlantic. Andrew Kidman was there and he was really generous to me with his write up in The Surfer’s Journal.

PA: Is that how you first got your foot in the door with The Surfer’s Journal?

CB: Yeah, exactly, I guess it kind of put me on their radar. Another friend, the photographer and filmmaker Patrick Trefz in Santa Cruz, was also really helpful. After Ireland, I had a handyman gig on the North Coast at Pigeon Point Lighthouse, and I was surfing the weird and sharky reefs there. Photos he took in the zone anchored a piece I wrote that was published in The Journal. A little while later, they were looking for an Associate Editor and I got the gig. So that was really fantastic, and actually from the lighthouse up there, with its maritime history, I got the vision for the boat I would eventually build, which I write about in Voyage of the Cormorant. You know, the vision, it just struck me and I was like, “I need to do that.” I built Cormorant while working at The Journal—that same boat that I now pile my kids into and take them out to explore the reefs around Carpinteria.

Sketch of Cormorant build, courtesy of Christian Beamish

PA: That’s a perfect transition because I want to ask you about the boat. You explained that you always grew up around the water but don’t necessarily come from a family of sailors or boat people. Being in the Navy, you talk about learning steelwork and other construction skills, and it sounds like you were already shaping boards, too. Did all those elements and acquired skills kind of come together in the construction of the boat? And did you have any prior boat building experience before the Cormorant?

CB: I started shaping in ’95 when I was up in Santa Cruz. I was in college and didn’t have the funds for a new surfboard, and I didn’t have the contacts like I had in Orange County. So I got a Sureform and a blank and shaped my first board under a tree in a friend’s backyard. I was exposed to surfboard shaping in my school years, watching Pautsch and Mike Lyttle from Huntington Beach, who was very helpful to me—he had spent time with Allan Byrne shaping in Japan back in the glory days, maybe late 70s, early 80s, when guys would go over there to shape boards and make some actual money. And he was shaping channel bottoms too, so that had a big influence on me.

So I knew all the steps to shape a board even though I’d never picked up a planer. But after that first one, I shaped my own from then on out. By 2001, I was getting pretty okay at it because that single fin I had over in Ireland, that was a cool little board. It was a 6’6” round pin, 40/60 rails—a very functional board that both Joe Curren and Hans Hagen rode to good effect. But as for boat building and being around boats, it was always a joke because I was in the Navy for five years, but spent all of 11 days as a passenger on a ship. Us Seabees wore green fatigues and combat boots, we were land-based.

PA: But I’m sure during this time, you must’ve acquired certain technical skills and the knowledge needed to navigate various tools and equipment that would later prove useful when building your boat.

CB: Yes, exactly. And also, one of the most critical things I learned in the Navy was the importance of close tolerances, and attention to detail. I learned the difference between an eighth of an inch and a sixteenth of an inch. And a perfect ninety degree angle and a fucked-up one. And in the U.S. Navy, you know, if you do something, they tell you very clearly whether it’s right or not—and that’s kind of refreshing. That concentration on precision that I took from the Navy was huge when I embarked on the boat project. Also, even though my family wasn’t into boats, it’s impossible to grow up in Newport Beach and not end up sailing a bit.

Kind of like in shaping, I had an intuitive sense of how boats functioned. And I think the first time I actually took Cormorant out and got her into the water, I realized that so much of that intuition I had with sailing comes from being a surfer. It’s all about drawing lines—your approach and knowing how to read the water.

PA: There’s a lot of surfer-shapers in the world today, and you’re a surfer-shaper-sailor, so can you expand on how these different engagements with water and how various vessels or craft inform one another for you?

Christian on the Cormorant

CB: I like the word intuition. There’s a through-line that has to do with curves. That is to say that there’s an element of cultivating an eye to recognize a good curve or an interesting curve. I suspect that someone who is not involved at all with surfing could recognize the beauty of a well-proportioned 7’2” pintail. With the boards I’m building—and I think I share this with a lot of shapers—we’re looking for that Michael Peterson moment (from the iconic Morning of the Earth frame grab of MP’s cutback) creating a board for beautiful, fluid carves. And I think I achieve that a lot more easily on a Twin Fin, and especially the mid-length, slightly longer ones. And how does that answer the question? As far as surfing and shaping go, I really love the craftsmanship of it all, and I really want to “shape,” so to speak, another boat. I’ve drawn the plans and things, but I also recognize that I can’t get bogged down by that right now.

PA: I’m sure that’s a big investment of time. How long did it take you to build Cormorant?

CB: Oh, I’d say about two years. I think I could probably do it in about six months now, but I remember I had a moment when I first got the plans for the boat and I was like, “Oh shit, what am I gonna do with these? I can’t read this.” And then you just go for it, and eventually a kind of 3D picture, or understanding of it all, starts to emerge and you figure out the steps.

PA: That’s insanely impressive, to build your first boat with no prior experience and then to embark on such a voyage. Pretty daunting I would imagine too.

CB: Absolutely, when I get back down to Baja once or twice a year, every time I drive that coast and I look out over that ocean, it just scares the hell out of me—that I did what I did.

PA: I can imagine. You talk about that feeling a bit in your book, when you finally get into the plane and are flying back over and you see the vast distance from Cedros to the mainland, which you sailed across in your little boat. And it just hits you, how vulnerable you really were down there while looking down on it from above. It’s crazy how that change of perspective really amplifies the magnitude of where you were, and what you were doing.

CB: Yes, absolutely. But I also realized, that when you’re in it, if you’re focused and on it, there’s not many situations that you can’t ride out of, no matter how scary they might be. But yes, the vastness of it all, it just really hit me.

PA: So upon ending your Baja voyage on the Cormorant, it sounds like you got right back into the bay and picked up shaping. What kind of newfound knowledge did you acquire on this sailing trip in terms of your understanding of hydrodynamics and craft building, and how did you then apply that to the boards you subsequently shaped? Were there any sort of unexpected revelations that you’d use to improve the boards you were shaping?

CB: Definitely, and it was indeed unexpected. There was something that had to do with the big, open water of the voyage. You know, Cormorant is a small boat (18-feet) but it’s a big surfboard. I tell people jokingly, the boat is basically an 18-foot, 12 channel pintail—especially in a running sea.

Upon returning, my pal up in San Francisco, Danny Hess—he’d been bugging to come up and surf Mav’s, and my view on that place had always been, “It’s a snuff-film, not for me… you know?” But he insisted, “No man, you’re gonna love it and I’ve got the perfect gun for you…”

And actually, on my first wave at Mav’s, I popped a rib that’s never been the same since, but I guess I had enough adrenaline that I still surfed the entire session. But the scale of that wave really lit me up—I loved it.

Also, in and around building Cormorant and doing these voyages, I was deep into exploring what Richard Kenvin was doing with Hydrodynamica and and his Simmons-style boards.

PA: Don’t you mention that the first board you shaped upon getting back in the bay after your voyage was, in a sense, your take on the Simmons?

CB: Yes, exactly. And I surfed some point waves down in Baja on that Simmons-style board and really was just marveling at that straighter run of rail, that grip of the keel fins, and the drive and functionality of the board. I covered the Eddie late in 2009 for Surfer Magazine, and I remember watching guys traverse the bowl on the giant, chunky day before they ran the contest, thinking—not to take anything away from the contemporary guys’ surfing—“they’re taking the Pat Curren line, the same as in 1957.”

There is a 1957 Pat Curren gun at the Surfing Heritage Museum in San Clemente (a very worthwhile trip for any surfer shaper interested in the lineage of surfboard design). The board is 10’7”, wide-point forward, a little bit of belly, hardly any rocker but the belly goes to vee— I mean, it’s a wicked piece of surfing equipment. And so I saw the plan shape and I envisioned cutting it off at 9’6”, which is a reasonable length for a Maverick’s gun. Of course, it would be sacrilege to touch an original Curren balsa, but if you were to take a similar plan shape and cut it off at 9’6”, that’s 13 inches up from the tail and all of a sudden you’ve got a fairly wide tail block, that would put the shape in the neighborhood of the Simmons design. Put a couple of keel fins on there, and now you’ve got this wide footprint, this big planing surface. So you’re gonna be able to get in early and project off the bottom.

Also, I remember the footage of guys in the late 90s on Rusty and Al Merrick guns, these super pulled pintails—they might’ve been 9’6” or whatever in length, but they were only about 6’8” in terms of usable surfing area with that super long pintail and pointy nose. So I increased the surface area on my boards and it was absolutely great... I had a real Maverick’s moment. And I’m not claiming that I’m a Mav’s guy, but during that winter of 2009-2010, I was kind of dipping my toes in the water out there.

Maverick's drop on self-shaped keel fin gun, photo by Todd Glaser

After my daughter was born in 2011, I went up there on a semi-big swell. I took off on a pretty good one from the peak with five guys on the shoulder just streaking straight down, right where I would’ve engaged my Pat Curren/Bob Simmons gun by putting it on rail and doing a bottom turn to power through and outrun the section. But instead, I had to straighten out and it felt like I took the entire Pacific right on my head. That was a really unpleasant experience. I don’t like the added layer of having to navigate the crowd in potentially deadly surf. I have two children—an 8-year-old girl, and a four-year-old boy—I’m busy at the town paper and shaping boards. So now I like to say that I surf small-big waves, and there’s a bunch of them around here.

PA: Getting back to the book, you reference the writings of Walt Whitman and John Muir as being sort of guiding companions while you were aboard Cormorant on your voyage. How did their style of writing, and your understanding of “Naturalism” influence the way you approached writing your own book?

CB: “Nature writing” can carry an air of privilege that makes me question it to some extent—being in a position to have the leisure time to go out and “be in nature.” But setting aside the socio-economic and racial aspects of who in contemporary society gets to “experience nature,” the actual experience of nature is, of course, endless in its splendor. I was keen to carve out the time in my life to take this voyage. I didn’t do it on a trust fund, and I lived it pretty close to the bone. Nevertheless, I still enjoy a lot of privilege given the historical context that informs our current moment, so I think it’s imperative to acknowledge or at least be aware of this fact when talking about this style of writing or these types of adventures.

PA: That makes perfect sense. I think in addition to that, there’s a lot of romanticizing at play here. When I read your book, I certainly romanticize the adventure elements of the story and the wanderlust that this type of writing inspires, and I’m curious to know if you were influenced in a similar way by some of the authors you were reading; the relationship between building your boat from the safety of dry land, at your home in San Clemente, versus actually getting it into open water and embarking on your journey. That’s a big jump, and I’m wondering how you reconcile the romanticized aspect of your voyage and if there was ever an “Oh shit” kind of moment, like, “What have I gotten myself into?”

CB: You balance it all, you know? I’ve always had this ideal of getting out into wild places. And I think it is supremely important to do that. I think of Wallace Stegner’s “Wilderness Letter,” in which he wrote, “We need wilderness preserved—as much of it as is still left, and as many kinds—because it was the challenge against which our character as a people was formed. The reminder and the reassurance that it is still there is good for our spiritual health even if we never once in ten years set foot in it. It is good for us when we are young, because of the incomparable sanity it can bring briefly, as vacation and rest, into our insane lives. It is important to us when we are old simply because it is there—important, that is, simply as an idea.”

I don’t want to be the Luddite who shakes his fist at the computer, it’s an incredible tool and I too have my face glued to the screen, I’m transfixed by the thing. But what’s more important, is remembering where we come from and all these fundamental elements of nature, places and natural systems in place, that have persisted, created and influenced who we are as people today. And so to be immersed and amongst nature is supremely important and a humbling experience from time to time.

And in terms of the writing process, I’ve always kept a journal and was journaling throughout my voyage, which I think is a great way to organize your thoughts, albeit a bit painful to look back on your musings and thoughts from 10-15 years ago. But in terms of structuring the book and my thought process, I really thought it would be the most boring book if it started off like “January 1st: taking off from San Diego, etc…” I wanted to break up that narrative somehow. And I think I did that by giving the reader a sense of my personal life in the first half of the book so that the story wasn’t quite so linear. Since I was writing in the first person, I felt that if I was going to expect someone to really sit down and read my book, then I’d better be honest about who it is the reader is dealing with.

I also think that as a writer, it’s important to be polite. And by that I mean, think carefully about what you’re saying. And make it make sense, and be clear. You are the host, and you’re asking a person to sit down and share your mind. So acknowledge that they’re there and write to them. That’s definitely something I kept at the front of my mind while writing the book.

PA: It’s interesting you talk about politeness to your reader(s), and I think it’s a testament to who you are, because it’s also something you touch upon more explicitly in your book vis-a-vis being a foreigner down in Baja and that feeling of imposition, particularly when you’re putting yourself in these vulnerable positions and then end up being rescued by a rogue fisherman or someone who then ends up welcoming you into his home and cooking a hot meal for you. It seems that you’re acutely aware of your presence in these people’s lives and their pure generosity.

CB: Hopefully the ideal doesn’t fall short of the reality. But I think that’s one of the benefits of putting yourself out there and making yourself vulnerable. And I suppose there’s a line, and at a certain point it’s just foolhardy. But there’s a lot of kindness in the world that doesn’t make the headlines, and Mexico is such a beautiful, colorful, culturally rich country, and the people are so incredible, so I’m glad that I could share that in my book.

PA: Can you talk about the therapeutic aspects of the voyage for you? You talk about your psychological struggles in the book and how the voyage kind of corresponded with you weaning yourself off Prozac. How important was the voyage for you in conquering some of your demons?

CB: I’ve received correspondence over the years from people who took some comfort in what I had written about my mental struggles in this book. I definitely don’t want to send the wrong message that you have to go on an epic voyage in order to better yourself, because I had really reached a point of critical physical depletion from maximum exposure being out in the desert, in the sun, on the water. It’s a brutal environment and it really wore me out.

In the springtime here on the West Coast, we get these Northwesterly winds that are nothing to trifle with out on the open water. And so it wouldn’t have been safe to continue, regardless of my condition, but definitely not given my physically depleted condition. I made 100% the right decision by calling the voyage when I did. And so all that is to say that I was pretty wrecked upon getting back, both physically and mentally. And then you combine that with going off Prozac, it wasn't an easy time. I’ve come to a better place in my life, and I’ve learned to recognize—I think, I hope, I ought to pray—the thought patterns that lead to the hopeless place of depression. So much of what we do is play out patterns of thought and responses to situations. Just patterns. I’m trying to change the patterns in my life to be a calmer, more hopeful, person—to be of service to my wife and children and to my community. It’s funny how troubles from one stage of life—I thought I loved somebody, maybe I did, I thought my heart was broken—come to be seen in a new light. It’s almost like you just have to hang in there long enough for whatever is troubling you to not matter anymore. But that can be a hell-of-a job. To quote Lao Tzu: “Nature does not hurry, yet everything is accomplished.” I like that.

PA: So what’s your routine like these days and what’s on the horizon?

CB: I’m 50 years old and so, at this point in my life, I’m like “Woah, okay, that’s no joke.” You start doing the math, in 20 years I’ll be 70, whereas 20 years ago I was your age. But I know I’m going to continue surfing, shaping, and writing—that’s for certain. Also help my children interpret the world around them. And love my wife, who has made a beautiful world for me to be a part of.

Christian, surfing in the 2019 Rincon Classic, photo by Glenn Dubock

Christian Beamish’s book The Voyage of the Cormorant is available through Patagonia. A selection of his surfboards are available through Pilgrim Surf + Supply.