Climbing Culture With Dana Gleason

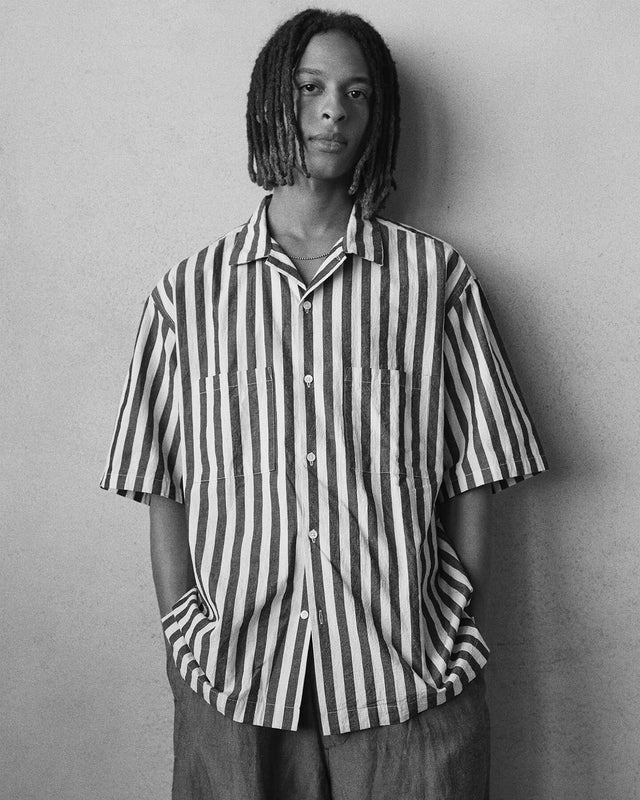

Dana Gleason founded the outdoor climbing pack brand Kletterwerks in 1975; due to business disagreements, he then left the company in the late autumn of 1978 with $6,000 and a sewing machine. From there, he went on to found a multitude of notable bag companies, including Mojo Systems, Mystery Ranch, and Dana Design. Then, after 35 years of silence, Kletterwerks reemerged in 2012 with Dana's son, D3, at the helm, modernizing the classically reliable packs. A self-described hippy (he claims he once even had the dreadlocks to prove it), Dana has pushed the quality of USA-made backpacks and climbing gear with his designs since the early '70s.

We recently teamed up with Kletterwerks to design our collaboration Pilgrim packs, with our custom color way (Midnight, Royal, Sand, and Black) and custom Pilgrim pennant/Kletterwerks logo (available in both our Amagansett and Brooklyn locations).

Here, Dana shares his stories and photographs of the history behind the climbing culture in the United States, the evolution of his pack designs, and how Kletterwerks has come full circle.

On his discovery of climbing...

"My relationship with the outdoors and climbing certainly preceded any bits of gear that I actually built. My parents had campers, and we went up to New Hampshire from Boston every summer. We would go out and do day hikes and things like that, and we didn't really think anything of it, we were just going camping."

What elevated camping from a hobby to something more?

"I got very interested in cross country skiing initially. Then I started ice climbing up in the White Mountains in New Hampshire before I even got started rock climbing. I was reading some of the books of the era, such as The White Spider, which was about the first ascent of the Eiger, and about a gentlemen who is often forgotten now, Gaston Rébuffat, who was the guy who did some the first ascents of the great north faces."

"It wasn't on TV, there were no videos -- there was a culture of, I guess these days we'd call it extremism. It was people who were doing crazy things in the mountains. It wasn't an everyday thing that teenagers of the time walked into -- so I guess I was a little weird."

What was that world like? Who were you hanging out with? What were you guys doing up there?

"We were just out having fun. We weren't thinking of things in philosophical terms of challenging ourselves. I didn't fall into a true group of people who climbed until I connected with some people who were starting up a climbing shop in Chicago of all places. That's when I connected with people for whom this was every day stuff."

"This was 1970. REI brought rock climbing into the country. But REI, which was started in 1938, was still just one funky shop in Seattle. You could get stuff through them, but in terms of getting stuff through local stores, there were none. This was the year Chouinard, what is now called Patagonia, founded Great Pacific Iron Works and they started producing chrome carabiners. It was the dawn of the climbing gear that we recognize as a generation. And these folks I had fallen in with, they were some hippy climbers, as I was -- we were all hanging out at Erehwon Mountain Supply [of which Dana was a founder], which is a chain still in existence now."

"We started Erehwon Mountain because we were importing our climbing gear in from Europe, and we didn't really have a huge amount of money for backing. We were just barely making ends meet. The Eurpoeans shipped us stuff and gave us credit. The stuff they were shipping were the dregs of the warehouse. They ended up sending us a half a warehouse full -- or I should say house, that we treated as a warehouse -- of stuff. We ended up opening up the store just so we could start selling it to someone, anyone. There weren't very many stores of this sort, especially in the midwest."

"Back then there was very little gear, and we still had unbelievably crude stuff. If it was wet out and you were climbing, you would pull a pair of wool socks over your climbing shoes, because it slipped less. I mean, this was really the Dark Ages of climbing. I think back to this and just shake my head that any of us survived. Climbing as we know it was literally being made up at the time. We were operating in a vacuum. We were making -- I believe this is the technical term -- we were making shit up."

"I had a job offer back in Massachusetts and thought about what I would do with a degree in physics. Also, that year student deferrments that kept you out of the draft had expired. The government instituted what was called the lottery system, and I got a number right in the middle. I didn't know if I was going to get impressed into the US military or not. I just decided I wasn't interested in college and I wanted to be doing things instead. I ended up taking a job with a shop that allowed me to be climbing every weekend and stay in contact with climbers. After a couple of years of that I had a couple of ideas for some things that I tried to build on a home sewing machine. This is in 1973 or so. It was totally frustrating experience because home sewing machines, well, they suck. I put two months worth of wages into a tailoring machine, not an industrial machine but the type of machine you see in the store fronts of dry cleaners but still heavy enough that I was able to build the piece I wanted. And friends saw that and asked if I could repair some of their gear. For the next two years I didn't build many new things but I did a lot of repairs. I have to tell you, repairing things is an excellent way of learning your craft. It's also an excellent way of figuring things out, like 'lifetime guarantees' depend on people not using the gear all that much, maybe pulling it out of the closet a couple times a year."

What are you thinking about when you design gear?

"For us, it's a little bit different because a lot of our customers use it hard and if they break it they have big consequences, which is why our stuff tends to be a little overbuilt."

"When we design we think about two things: In the first few years, we thought about how to build it so it would not break; it was a huge concern. And we knew very well what would break from doing repairs of people's gear. I was hugely fortunate that I did not have an education within the business; we ended up learning and making this stuff up for the first decade."

"The way we built the original Kletterwerks, we were taking what were essentially soldering guns and drawing the patterns directly on the fabric and then cutting the fabric with a four or five hundred degree blade. I'll submit we were sniffing nylon fumes and such, which I'm now highly sensitive to. The first year or two of Kletterwerks I cut almost everything. When we used these soldering guns, which were about four or five pounds each, they would get to hot to hold. So we would stick them in the freezer next to the cutting table and pull out the next one, which was virtually to cold to hold, and then be cutting away for another twenty or thirty minutes with that. We were very hardheaded, and getting stuff built right was the very first job. And then the second job, which then became the first job, was how do we build it so that people like it?"

[The first time 'round with Kletterwerks.]

"There's a generation even older than I am that really pioneered this stuff, I would say I am out of the second generation. It's been one hell of an amazing ride. And with Kletterwerks as being seen as cool enough to bring back around -- I'm amazed. I'm truly amazed that I have one of my sons doing the design work to bring it back with a little more modern materials."

[All photos courtesy of Dana Gleason.]